The Federal Bureau of Investigation has dramatically increased its use of polygraph tests on its own employees—a shift that has raised concerns both inside and outside the bureau. The move, reportedly aimed at identifying internal dissent and media leaks, is being carried out under the leadership of Director Kash Patel. Former and current employees allege that the polygraphs are being used not for security clearance purposes, but to assess loyalty and root out criticism of Patel or his administration.

According to The New York Times, dozens of FBI staffers have been subjected to polygraph screenings. These include a senior employee questioned about whether they had said anything negative about Patel, and another scrutinized for possibly leaking details to the press regarding Patel’s unusual request for a service weapon. Some of the lie detector tests reportedly took place despite a lack of direct evidence of wrongdoing, suggesting a broader intent to monitor internal attitudes.

This marks a clear departure from established FBI precedent. Historically, polygraph tests were reserved for pre-employment screening or probing allegations of espionage, betrayal, or other high-level security breaches. Now, their use appears to be shifting toward internal discipline, ideological control, and containment of leaks.

Former FBI official Michael Feinberg, who ran the Norfolk, Virginia office until earlier this year, said he was threatened with a polygraph test simply because of his friendship with Peter Strzok. Strzok, a counterintelligence official involved in the Trump-Russia investigation, was removed from the bureau after text messages emerged in which he criticized Donald Trump. Feinberg, who never took the polygraph, resigned and later publicly criticized Patel and his deputy Dan Bongino for placing politics ahead of professional competence.

Critics say the bureau under Patel is increasingly resembling Cold War-era intelligence agencies, when both the FBI and CIA used polygraphs and loyalty tests to question employees about their political affiliations or so-called “un-American” beliefs. These methods, common during the McCarthy era, often relied on coercion and vague accusations, and were widely criticized for suppressing dissent and punishing ideological nonconformity.

James Davidson, a retired FBI agent with over two decades of service, warned that Patel’s approach risks damaging the bureau’s integrity. “An FBI employee’s loyalty is to the Constitution, not to any one director,” Davidson said.

The expanded use of polygraphs isn’t isolated to the FBI. Other federal departments, including Homeland Security and Justice, have also reportedly ramped up internal screenings following leaks to the press. These changes appear to be part of a broader initiative launched during Donald Trump’s second term, led by the Department of Government Efficiency—a White House agency chaired by Elon Musk—aimed at reshaping the federal workforce.

This initiative has also resulted in large-scale job cuts. Following a Supreme Court ruling that cleared legal challenges to the restructuring plan, the State Department has begun informing employees of widespread layoffs. An estimated 15% of domestic staff will be let go in what Secretary of State Marco Rubio has called a push for a “leaner, faster” agency. Yet critics argue this purge is based less on organizational streamlining and more on political priorities. Foreign language expertise and regional knowledge are not guaranteed protection under the cuts, which are based on office-wide functions rather than individual performance.

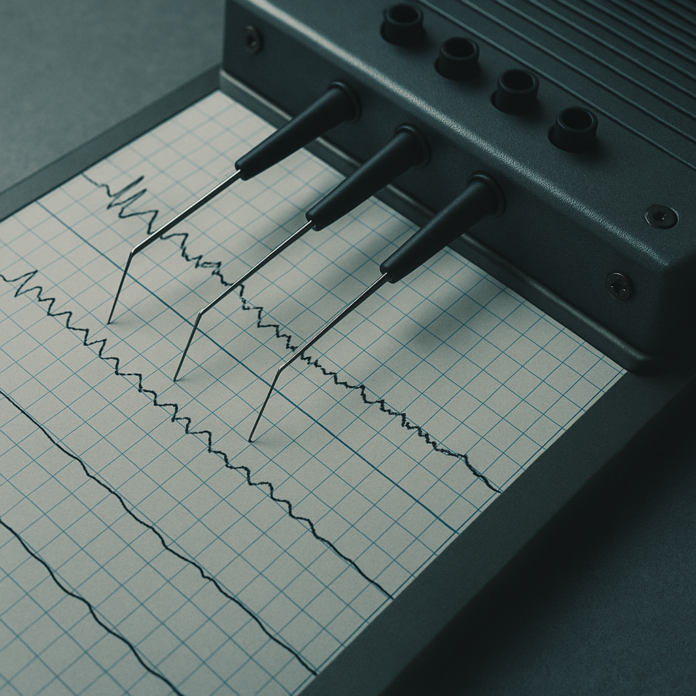

While former intelligence officials have long expressed skepticism about the reliability of polygraph tests, their use persists in federal security vetting. Polygraphs measure physiological signals—such as heart rate, blood pressure, and perspiration—but do not definitively detect lies. Reviews by the National Academy of Sciences and American Psychological Association have questioned the scientific validity of the tool. Yet its psychological power is well documented: individuals frequently confess details under pressure, even when no deception has occurred.

In authoritarian regimes such as Russia and Iran, similar tactics have long been used to root out dissent. Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) employs polygraphs and other psychological methods in counterintelligence operations. Iran often uses ideological and religious vetting in its intelligence services. In China, while polygraphs are less common, ideological screening and digital surveillance serve the same purpose. Even organizations like the Church of Scientology have drawn parallels through their use of the “E-Meter,” a tool akin to a lie detector, to interrogate members about loyalty and perceived betrayal.

The growing reliance on polygraphs and loyalty tests within U.S. federal agencies appears to echo these practices, raising concerns about the erosion of democratic norms. Former CIA veteran Brian O’Neill noted that polygraph campaigns often generate a chilling effect within agencies, suppressing internal dialogue and discouraging employees from flagging legitimate concerns.

Historically, U.S. leak investigations have rarely resulted in criminal charges. Cases like the exposure of CIA officer Valerie Plame or the leak of diplomatic cables by Chelsea Manning sparked major political controversy, but such responses were exceptions. Most investigations into leaks fade without resolution. When punishment does occur, it is often uneven, depending more on political fallout than legal standards.

As the Trump administration pushes forward with its ideological reshaping of the federal bureaucracy, it remains to be seen how these tactics will impact government function and morale in the long run. The next phases of layoffs and investigations are expected to expand to other departments now that legal obstacles have been cleared. Inside the FBI and beyond, employees are increasingly uncertain whether speaking their minds—or even maintaining the wrong friendships—could make them targets.

This image is the property of The New Dispatch LLC and is not licenseable for external use without explicit written permission.