The United States government is taking new steps to reshape how it manages some of its Cold War–era plutonium, offering energy firms the chance to convert the material into reactor fuel. The Department of Energy has issued an application process allowing qualified companies to seek access to up to 19 metric tonnes of surplus weapons-grade plutonium. The Financial Times reported that this material could be repurposed for use in advanced nuclear reactors under strict federal supervision.

The initiative reflects Washington’s renewed drive to strengthen domestic nuclear energy production and reduce reliance on Russian uranium supplies. It also connects to broader efforts to meet the growing demand for electricity as data centers and artificial intelligence systems expand nationwide. The policy appears aligned with President Donald Trump’s push to boost domestic energy output and maintain U.S. leadership in nuclear technology.

Among the companies expected to apply are Oklo, a startup backed by OpenAI’s Sam Altman, and Newcleo, a France-based nuclear innovation firm. Both specialize in small, next-generation reactor designs that can potentially use recycled nuclear material as fuel. Their participation could help test whether older plutonium can serve as a viable input for new reactor types that aim to produce cleaner, more efficient energy.

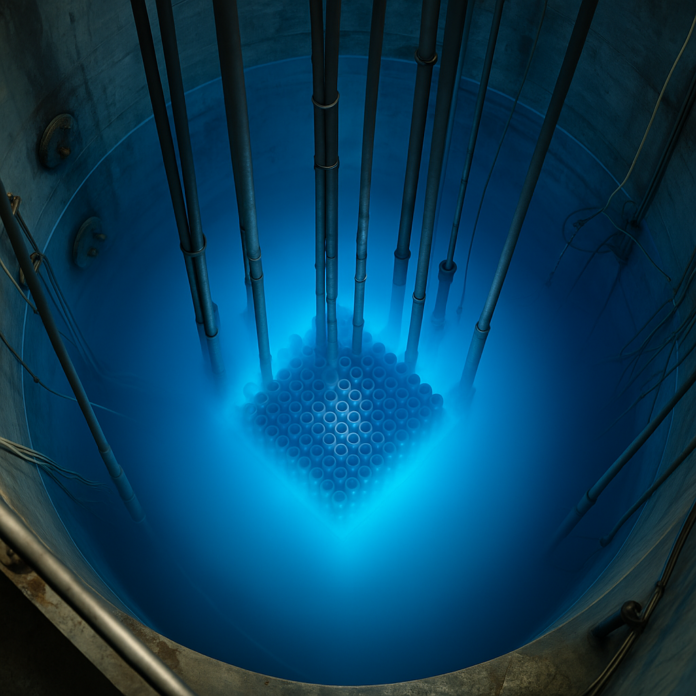

The United States currently maintains a large stockpile of plutonium declared surplus to defense needs. For decades, the question of what to do with it has divided experts and policymakers. A previous plan to turn it into mixed-oxide fuel for civilian reactors was abandoned in 2018 after construction delays and budget overruns at the Savannah River Site in South Carolina. Since then, the government has relied on a “dilute and dispose” strategy, packaging the material for burial in New Mexico’s Waste Isolation Pilot Plant. The new Department of Energy program reopens the conversation about using some of this material for energy generation. Any commercial use would require approval from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, oversight from the National Nuclear Security Administration, and coordination with the International Atomic Energy Agency to ensure safeguards and transparency.

Turning plutonium into reactor fuel presents technical, security, and diplomatic challenges. The material requires special handling and transportation procedures, and reactors must be modified or newly designed to accommodate it. Communities near fabrication and disposal sites, such as those around Savannah River and Carlsbad, New Mexico, may face new safety and logistical concerns, even as they stand to gain jobs and investment. From a global perspective, Washington’s choice will be closely watched. France and Japan already use plutonium-based fuel under tight controls, while the United Kingdom and Russia have pursued their own pathways with mixed outcomes. U.S. officials will need to balance domestic goals with the message they send abroad about managing weapons-origin materials and maintaining non-proliferation commitments.

The Department of Energy’s application release is only the first step. The next indicators to watch include formal requests for proposals, early industry responses, and signals from regulators about how licensing might proceed. Congress will likely weigh in, given the cost and political sensitivity tied to past plutonium projects. If the initiative advances, it could offer a way to reduce an expensive stockpile, support the country’s clean energy transition, and test new reactor designs that promise higher efficiency. Yet the path forward remains uncertain—caught between technological promise, public caution, and the long shadow of nuclear history.

This image is the property of The New Dispatch LLC and is not licenseable for external use without explicit written permission.