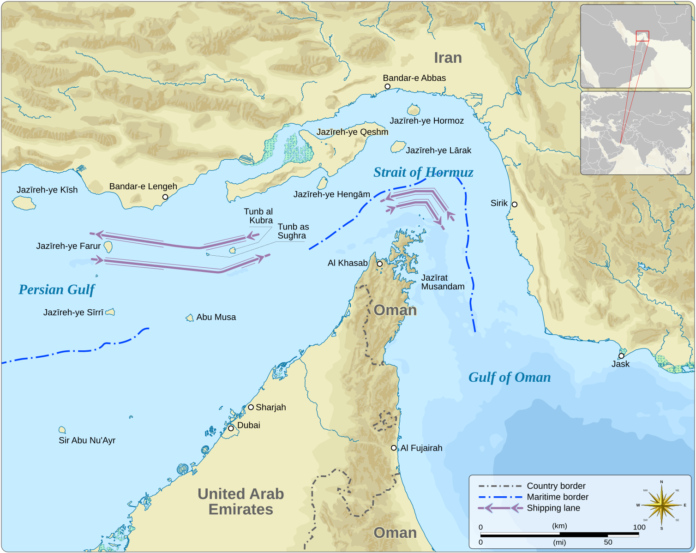

The Strait of Hormuz remains a central artery for the global energy trade. This narrow stretch of water between Iran and Oman serves as the main route for oil and gas exports from the Persian Gulf, funneling roughly 20 million barrels of crude oil each day—nearly one-fifth of worldwide consumption. It also supports a large share of global liquefied natural gas shipments. Just 21 miles wide at its tightest point, the strait is both vital and vulnerable, a fact that has grown more pronounced amid recent geopolitical friction.

The United States Energy Information Administration (EIA) has reported that over one-third of the world’s seaborne oil exports passed through Hormuz in 2023. Most of these shipments were destined for Asia, with countries like China, India, Japan, and South Korea accounting for the majority of the demand. India reportedly receives over 2 million barrels per day through Hormuz, supplying around 40% of its oil needs.

Although the United States imports far less crude via the strait—under 0.5 million barrels per day—the region’s volatility affects global pricing. Because oil is traded in a global market, even distant supply shocks ripple across economies.

Market sensitivity to tension in the region was evident in 2024, when a brief flare-up in the Gulf pushed Brent crude prices from $69 to $74 per barrel. Analysts caution that if transit through the strait were seriously disrupted, oil could quickly climb to triple digits. The risk of escalation resurfaced in June 2025 after Iranian lawmakers introduced a measure to block the strait in response to reported U.S. airstrikes on nuclear infrastructure. Though similar threats have been made in the past, Iran has never acted on them, likely due to the economic blowback such a move would trigger.

Past confrontations offer a precedent. During the 1980s, the Iran-Iraq War gave rise to the so-called “Tanker War,” when both countries targeted oil tankers transiting the Gulf. Today, any attempt to close the strait would likely involve similar tactics—mining lanes, harassing shipping, or blockading tankers. Naval forces in the region, particularly the U.S. Fifth Fleet based in Bahrain, remain a key deterrent against such actions.

Options for bypassing the strait are limited. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates operate pipelines that connect their oil fields to export terminals beyond Hormuz. These include Saudi Arabia’s East-West pipeline, which carries crude to the Red Sea, and the UAE’s line to the port of Fujairah. While these routes can handle a combined 6.5 million barrels per day, much of that capacity is already in use. Iran has a pipeline to its southern coast at Jask, but it is smaller and not fully utilized. Combined, these alternatives can only handle a fraction of the oil that currently moves through the strait.

The geography of the strait adds to its fragility. Iran controls the northern coast, while Oman and the UAE hold territory on the southern side. This makes the region a persistent flashpoint. Beyond military and political concerns, major energy importers—particularly in Asia—have a vested interest in keeping the waterway secure. China, which buys a majority of Iran’s sanctioned oil exports, has taken on a more visible role in regional diplomacy in recent years.

Analysts widely agree that a complete shutdown of the strait would damage Iran’s economy as much as others. While the rhetoric remains heated, the likelihood of full closure is considered low, though the mere possibility is enough to unnerve markets. Online, users continue to speculate about potential moves, with international media closely watching every development.

With so much of the world’s energy moving through a single chokepoint, the stability of the Strait of Hormuz remains a barometer for both economic confidence and geopolitical risk.

Image is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license and was created by Goran_tek-en.