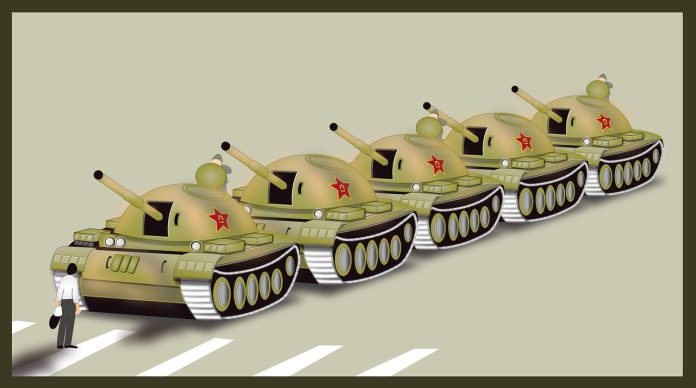

Xu Qinxian (August 1935–January 8, 2021) was a major general in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) who became one of the most prominent known cases of a senior Chinese military commander refusing to carry out orders connected to the use of force against civilians during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. His decision, made while commanding one of the PLA’s most elite formations, led to his removal, imprisonment, and erasure from official history, while earning him lasting recognition among those who regard his actions as an act of moral courage.

Xu was born in Ye County (now Laizhou), Shandong Province, to a modest family. He joined the PLA as a young man during the Korean War era, initially serving in communications roles before steadily rising through the ranks. Over decades of service, he developed a reputation as a disciplined and capable officer with a strong grasp of modern, mechanized warfare. By the 1980s, he had risen to major general and assumed command of the 38th Group Army, headquartered in Baoding near Beijing. The 38th was widely regarded as one of the PLA’s best-equipped and most politically sensitive units, tasked with protecting the capital and its leadership. Xu was also known to be close to then–Defense Minister Qin Jiwei.

In the spring of 1989, as student-led demonstrations calling for political reform and an end to corruption spread through Beijing, China’s top leadership moved toward a military response. Martial law was declared in mid-May. During this period, Xu—who was hospitalized with kidney-related health issues—received orders to mobilize the 38th Group Army toward Beijing to help enforce the crackdown. According to multiple accounts, senior officers from the Beijing Military Region pressed him to comply.

Xu refused. He initially cited the absence of written orders and his medical condition, but he later made clear that his objection was principled. He argued that the PLA should not be used against the people, that the situation in Beijing was politically complex rather than militarily defined, and that deploying troops against civilians—particularly students intermingled with ordinary residents—would permanently damage the army’s legitimacy. Statements attributed to him during this period and later at trial include his insistence that the People’s Army had never been used to suppress the people and that he would rather face personal punishment than become a “criminal of history.”

The refusal alarmed Party leaders, who feared hesitation or disobedience within the armed forces. Xu was promptly removed from command, detained, and later court-martialed in a closed military trial in 1990. He was expelled from the Chinese Communist Party and sentenced to five years in prison, reportedly serving much of that term in facilities associated with Qincheng detention. The sentence was severe enough to end his career but comparatively lenient given the gravity with which insubordination was treated at the time.

After his release, Xu lived quietly under restrictions in Shijiazhuang, Hebei Province, avoiding public life until his death in January 2021 at the age of 85. Meanwhile, the 38th Group Army, under replacement leadership, was deployed during the June 3–4 crackdown that resulted in the deaths of hundreds, and possibly thousands, of civilians.

In late 2025, a video recording of Xu’s 1990 military trial surfaced publicly, renewing attention to his case and offering rare insight into internal dissent within the PLA during the Tiananmen crisis. The footage showed Xu calmly defending his refusal and reiterating that political problems could not be solved through military violence.

Although Xu Qinxian remains absent from official Chinese histories of 1989, his stand has endured in exile communities, among historians, and among those who see in his actions evidence that individual conscience can persist even within highly authoritarian systems. His legacy is that of a soldier who chose personal ruin over obedience to an order he believed would stain both himself and the institution he served.

Image is in the public domain and is licensed under the Pixabay Content License.